According to petsinclude.com, the cultural revolution was in chronological order the last event that mobilized art for political purposes in China and reaffirmed the commitment to make it an instrument of the class struggle at the service of a national and proletarian, alien culture as much from the conventionalism of the old cultural elites as from the formal avant-gardes of the West.

Perhaps the culminating moment of the ideological travail that lasted from the movement of May 4, 1919 was marked, when a first decisive trend towards a genuinely Chinese and popular culture emerged, which did not suffer a supine adhesion to Western civilization. The refusal that the notion of “modern” must necessarily identify itself with the West and that in order to improve its conditions, China should operate a fracture in its history, regardless of the internal economic, social, cultural reality, has informed the most recent political choices, with the importance attached to the agrarian economy and the rural world, in the concern that a process of industrial transformation with an eminently urban character would upset the entire Chinese social order with an artificial structure, without being able to give, on the other hand, appreciable profits in the absence of adequate “tertiary” equipment. Hence the program of gradual industrialization and its organic integration into the rural world, with the implicit evaluation of the peasant element in terms of the proletariat. This political orientation has promoted a greater balance between city and countryside and has enhanced the rural world, rationalizing its settlements and coordinating their activities, with positive repercussions on industries and rural artisans who have recorded increasing levels of production both in series and in individual products. At the same time, the products of minority nationalities entered the distribution circuit, apparently more and more uniform with those of China.

Among the traditional handicrafts, ceramics, jades, ivories, bones, carved woods and fabrics dominate. A revamp of the design has generally not been encouragedand the artifacts have mostly repeated classical forms and motifs, already largely conventionalized in the last century. This has undoubtedly had harmful effects on the high-quality foreign market, but also the advantage of making goods such as porcelain available to large social strata, both internally and abroad, previously destined for more customers. restricted. A late Ch’ing period production (1644-1911) was revived in the ancient pottery center of Ching-tê ch’ên, whose kilns have been reactivated since 1951; Nineteen completely renovated factories operate in the city today, employing about thirty thousand potters, also for the production of industrial porcelain. Among the other artisans, glass has been intensified, according to the most up-to-date technologies; gl ‘ plants in the Liao-ning province are among the most modern and ensure industrial supplies. The whole craft market is held by the China national arts and crafts import and export corporation.

A kind of pre-eminent artisan tradition, which has now assumed, under Western influence, an autonomous artistic dignity, is represented by sculpture in stone or marble, mostly of the European school. There are distinguished artists trained in France, such as Hua T’ien-yü (b.1902), Liu K’ai-ch’ü (b.1904), Liao Hsia-hsüeh (b.1906) Wang Ling-i (no. 1909). By these and their disciples commissions have been carried out for portraiture or monumental statuary, celebrating the heroes of the new China. The style, beyond the more recent formal adhesion to socialist realism, continues to highlight a taste for the linear, graphic element, which is a sure Chinese artistic heritage and helps to avoid triumphalism or empty solemnity in favor of expressive values interior.

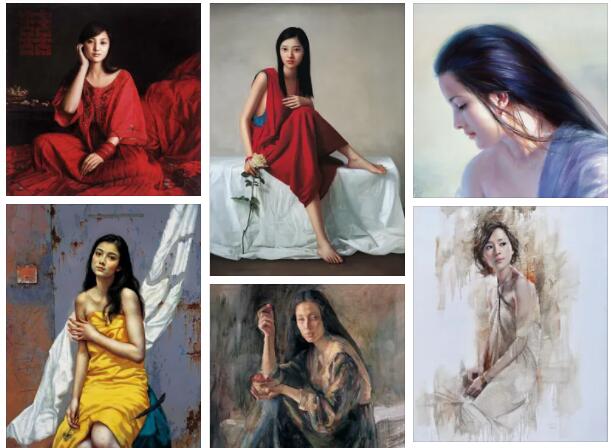

The artistic tradition now coexists, in terms of techniques and styles, alongside the new genres and trends of world art. The pictorial production that remained faithful to the school of the “masters” of the twentieth century is oriented towards expressionistic and spatial values, such as Wu Ch’ang-chih (1844-1927), Ch’i Pai-shih (1863-1957), Hsü Pei-hung (1894-1953), Ch’ang Ta-ch’ien (b.1899). These are works that have preserved in the use of ink now a calligraphic style for outlines, now a stain technique, and have developed their themes (landscapes, etc.) with the continuous essentiality of chromatic and illusive means. Calligraphy continues to be cultivated and periodic exhibitions are opportunities for encounters and comparisons with Japanese calligraphers, who are now the only ones outside of China, to cultivate the tradition of ideographic art. Taiwanese traditional style painting is perhaps nourished by greater sentimental resonances, compared to that of the continent, also for the re-enactment of landscapes and architectures of places from which the artists felt they had escaped; but, especially the younger personalities – we mention Ching Sung (born in 1932), Liang Ye-koon (born in 1935), Tsang Mei-chung (born in 1937) – have developed an art in which tendencies towards a figurative or abstract language that is now a common expression of international art. The same applies to overseas Chinese artists – from Hong Kong, Singapore, Indonesia, etc., or active in Europe and America -, many of whom retain an unmistakable Chinese expressive or stylistic imprint.

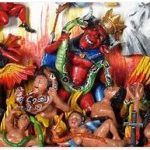

For the artists of the continent, Yenan’s directives of 1942, the movement of the “hundred flowers” of 1956, the “great leap forward” of 1959, were the phases of an awareness of the political value of culture and art, first in the wake of socialist realism of Soviet formulation, then according to a growing adaptation to Chinese cultural reality. In the service of the resistance struggle and of the revolutionary movement, then of the socialist construction, a large number of artists have produced paintings, drawings, woodcuts, used above all as matrices for the high circulation of posters, illustrated books, stamps, in single compositions or in series, which also made use of collagesphotographic. Many works have been presented and sold abroad, thanks to organizations such as Guozi shudian, the Foreign languages press, the China philatelic company. The themes have now illustrated the Chinese artistic heritage, also through new archaeological discoveries; now they have presented the history of the twentieth century and celebrated figures from Lü Hsün to Mao Tze-tung. The great world movements were commemorated, from the Paris Commune to the October Revolution, to the national liberation struggles fought in the various continents and countries. Important artistic personalities were Li Hua, Liu T’ieh-hua, P’an Jên, Chang Yung-hsi.

An important sector is constituted by the illustrated narrative, in particular by the genres that are included in the “comics” for the characteristic interdependence established between the graphic element and descriptive and dialogic captions. These are pamphlets, albums, books, with series of plates in black and white or in color, illustrating adaptations of novels and short stories, mostly inspired by the struggles against the old society, liberation and revolution. A little bright red staris the adaptation of a novel by Li Hsin-tien among the last presented. The graphic medium facilitates the dilution of history into the heroic myth, of the chronicle in the celebration of heroisms and daily sacrifices. Themes of costume satire have also appeared, as well as revisits of old stories in the key of current political allegory. The pedagogical requirement is twofold: literacy and culturalization, not only at the level of childhood but of adult readers.