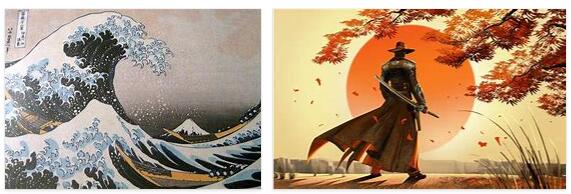

The development of Japanese art in the sec. VII and VIII coincides and takes place in the Nara period, especially starting from 702, in which adherence to the institutions and cultural heritage of Chinese civilization is greater and more conscious. Starting from the first decade of the century. VIII the presence of Chinese culture in Japan, as elsewhere in Far East Asia, was realized with a real graft on local traditions already contaminated by the origin of Sino-Korean formative characters. The new capital was founded in 710 in Heijō-Kyō (today’s Nara), after the previous offices of Naniwa (Ōsaka) and Fujiwara, taking inspiration for urban planning and architecture from the model of the Chinese city of Ch’ang -an, capital of the Han and T’ang dynasties. The traditional use of only wood in buildings, if on the one hand made it more difficult to translate thefrom another it was extremely profitable for the freedom of solutions and often with results of authentic originality. Among the large temples with plants with different patterns that arose in the Nara period, the Yakushi-ji, the Tōdai-ji, with its characteristic pavilion (shōsōin), a sort of deposit of the treasure derived in the form from the ancient shintō granary; the Kōfuku-ji, the Taimadera, the Tōshōdai-ji and the Eizan-ji.

Of these and other temples, isolated constructions remain of the time, such as pagodas (which here assume value equivalent to that of the stūpa) and Halls (pavilions) in the variety of functions assigned to them. On the impulse of this constructive fervor the arts and crafts flourished thanks to the contribution of artists and workers of the monasteries themselves. Like architecture, sculpture and painting were also inspired by the Chinese sources of T’ang art and were realized above all in the religious sphere of Buddhism. To substantiate the meager documentation of Nara painting, limited in its greatest expression to what remains of the paintings that decorated the Kondō of the Hōryū-ji, are now added the mural paintings of the tomb of Takamatzu-zuke in the village of Asuka, discovered in 1972, whose dating oscillates between the end of the century. VII and the beginning of the century. VIII.

According to itypeauto, these paintings represent two opposing groups of “ladies” and “valets”, while the side walls represent fantastic animals linked to Chinese cosmic symbolism. The realism of the figures, the details of the hairstyles and clothing, the richness and vivacity of the colors, the safety of the drawing, show an unprecedented knowledge, style and technique in Japanese painting of this era, whose matrix must be sought in the tradition of T’ang painting, enriched with Central Asian elements and interfering with a Sino-Korean composite style. emakimono: the first scroll painting appears only in 735 through the Japanese copy of the Chinese sutra Ka ko-Genzai-Inga-Kyo (Cause and Effect in the Past and Present), in which the painted scenes are an elaboration of Chinese painting by landscapes and figures of the T’ang era.

The realism of the painting passage from Takamatzu-zuke’s tomb is the only contact note with the lively realism offered by the Nara sculpture, which marks, in this sense, a stylistic evolution compared to the production of the previous Asuka period. In addition to the bronze works of the early Nara period, which already show a strong Japanese interpretation of the deeply assimilated Chinese T’ang style (statues of Sho-Kannon and Yakushi with the acolytes Gakkō and Nikkō; Nara, Yakushi-ji), important are those performed in dry lacquer and clay in the second period (Tempyō). In dried and painted clay are the statues of the two Bodhisattvas who make up the Triad with Fukūkenjaku Kannon (in dry golden lacquer) in the ancient building (Hokkedō) which constituted the first Tōdai-ji in Nara, later destined to collect works of sculpture, such as the gigantic statues of Kichijōten, of Benzaiten, of the Four Guardian Kings. The greatest examples of painted dry lacquer sculpture (a technique that allowed to obtain variety of effects and precise description of details) are found in the Kōfuku-ji of Nara (statues of the Celestial Guardians and the Disciples of Śākyamuni). In painted dry lacquer there is also an important work of Nara portraiture (the Priest Ganjin in the Tōshōdai-ji of Nara), whose genre finds variety of expressions in the rich production of wooden masks for the Gigaku dance (a large number are preserved in the temples), where the taste for the caricature and the grotesque is often accompanied by acute psychological notes. The technique for one-piece wood carving (ichiboku-bori) gives rise to a new style, which will partly characterize later Heian sculpture.